The Commonwealth’s taxpayers fork out at least $8,000 every month for a San Diego company to drive around up to eight people a month in need of Medical Referral Services Office support. According to the procurement record for Marianas Connections, the vendor charges the Commonwealth $750 per patient per month after the retainer agreement of eight. There is no limit to this provision, according to the contract.

Marianas Connections is the dba for DorisAnn Aldan Atalig. Ms. Atalig is the wife of Secretary of Finance David Atalig, Jr., the official who authorizes obligations and payments to vendors such as his wife. And according to the procurement record, which the Commonwealth Healthcare Corporation disclosed to Kandit from an Open Government Act request, Ms. Atalig got the lucrative contract through sole source procurement. This means the Torres administration awarded her the contract without Ms. Atalig having to compete for it under the government’s procurement regulations.

“I request approval to execute a sole source contract with DorisAnn Aldan-Atalig d/b/a Marianas Connections to provide transportation and logistical support for medical referral patients referred to health facilities in San Diego, California,” a September 9, 2021 letter signed by Gov. Ralph Torres to acting director of procurement services Francisco C. Aguon. “Such support is to include transportation between the airport, lodging, and medical facility for patients and escorts. Such support services are also to include transportation to grocery stores and other points. Support services may also include obtaining medical equipment, pharmaceuticals and other supplies and various other duties.”

Mr. Atalig appears to have conflicted himself out of the procurement; others signed the procurement records in his stead.

The documents Kandit requested regarding Marianas Connections do not indicate how much the Commonwealth government has either obligated or spent on the company, though it is expected monthly obligations have far exceeded the retainer rate of $8,000 a month. To be clear, even if Marianas Connections were to have only eight clients under the MRSO in San Diego in a month, that would mean the Commonwealth’s taxpayers pay the company $1,000 a month to provide chauffeur services per person.

Gov. Torres himself was the expenditure authority for the vendor, according to the contract he entered into with Ms. Atalig on September 28, 2021. The contract was effectuated after an audit by the Office of the Public Auditor that slammed MRSO for a number of financial issues, and before the transfer of MRSO from the governor’s office to the CHCC took effect in Fiscal Year 2022. FY 2022 began on October 1, 2021, just three days after Mr. Torres gave final approval on the contract.

While the sole source procurement for Marianas Connections to operate as the transportation vendor in FY 2022 appears to be a continuation of services the company provided from previous fiscal years, it is unclear whether the company and the Commonwealth government previously were under contract. An OPA audit from 2021 called the matter into question.

The 2021 audit of the CNMI Medical Referral Services Office revealed exponential overspending, millions in questionable petty cash expenses by the Guam and Hawaii offices, service contractors paid millions without contracts, a spike in millions in illegal promissory notes the year Ralph Torres was elected governor, and the illegal transfer of the MRSO from the Commonwealth Healthcare Corporation to the Office of the Governor.

“OPA found that MRSO does not have standard operating procedures for any of the three offices in operation,” the audit, published by the Office of the Public Auditor in 2021, states. “The lack of internal controls, such as standard operating procedures, to ensure an affordable, effective, and equitable program poses an ongoing potential risk for fraud, waste, and abuse.”

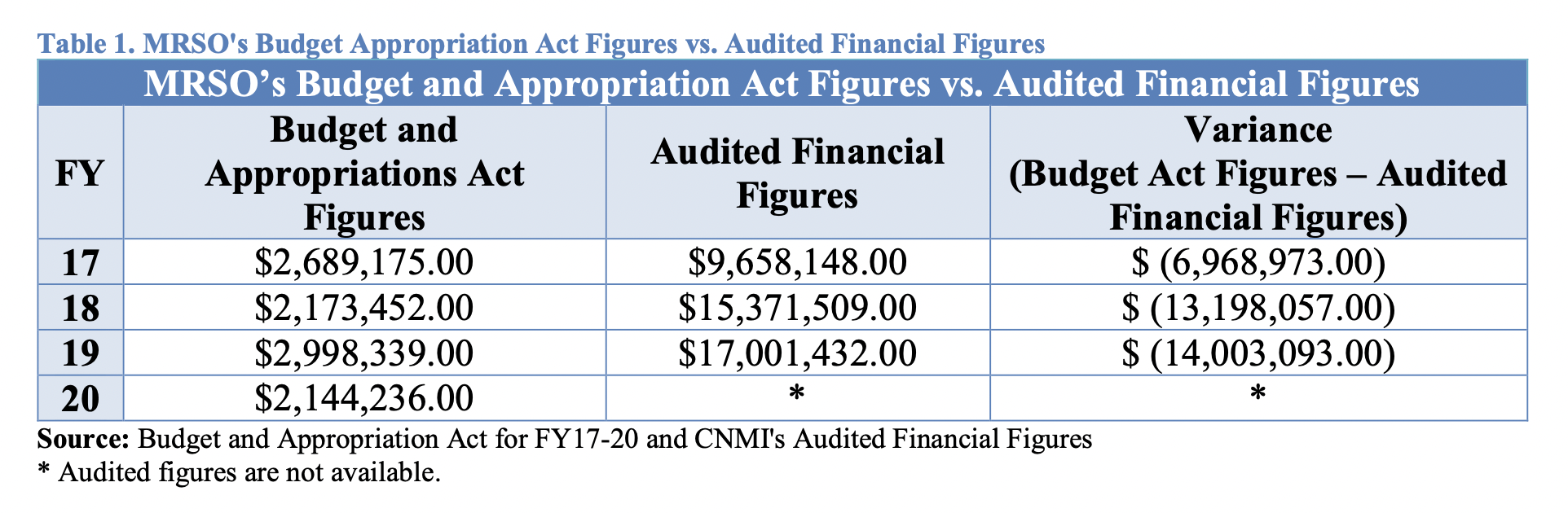

MRSO overspent by 500% of its budget

“MRSO has been an entity under the Office of the Governor whereby funds can be reallocated to cover expenses without legislative oversight,” the audit states. “As a result, a large variance between what was appropriated and the actual expenditures increased each fiscal year.”

A chart of the audited financials of the MRSO from Fiscal Years 2017 through 2019 – all during the Torres administration – shows the office overspent by up to more than 500 percent of its budget. In FY 2017, MRSO was budgeted $2.6 million, and spent $9.6 million. Overspending grew the following fiscal year, with MRSO spending $15.3 million from a $2.1 million budget. In FY 2019, MRSO’s spending peaked at $17 million on a $3 million budget.

Expired contracts

“Based on the contracts provided by MRSO on July 9, 2020, OPA discovered that MRSO’s contracts and agreements have expired for two vendors for medical utilization, two for transportation and logistics support, and six for hotel accommodations,” the audit states. “OPA also requested from the Department of Finance (DOF) any updates pertaining to all of MRSO’s contracts. However, no updates were provided.”

Vendor 9’s drawdown of millions

The audit revealed an arrangement between the CNMI government and one vendor, identified only as Vendor 9, whereby the vendor had direct access to a government bank account. According to the audit, Vendor 9 had withdrawn $3.3 million – about 50 percent more than the agency’s annual budget – from a revolving fund, with sparse documentation to justify the expenses. The audit states:

“The CNMI Government contracted Vendor 9 for discounted services on medical expenses incurred by CNMI medical referral patients. In return, the contract grants Vendor 9 the authority to automatically withdraw monthly payments through Automated Clearing House (ACH) from a revolving account for all claims paid on behalf of the CNMI Government. In addition, a 15% access cost fee for all claims paid by Vendor 9 is charged and automatically withdrawn monthly.

“As of April 30, 2021, OPA noted that Vendor 9 has withdrawn an estimated $3.3 million from the revolving account. Through MRSO and DOF, Vendor 9 provided OPA documentation claiming the total “savings” incurred by the CNMI government as of March 31, 2021. However, OPA could not validate claims of CNMI savings due to the limited data provided by MRSO and DOF.

“To ensure effective internal controls are implemented for accurate reconciliation, OPA requested for documents pertaining to Vendor 9 that should have been maintained and verified at MRSO and DOF. However, OPA was notified that the listing of documents requested were forwarded directly to Vendor 9 by both MRSO and DOF. This included a listing of:

- invoices paid by Vendor 9 for individual medical claims that references to the monthly automatic ACH withdrawals;

- monthly funds transfer confirmations indicating the amount automatically withdrawn; and

- invoices for the 15% fee automatically withdrawn from the revolving account. Although OPA received a listing of the claims paid on behalf of the CNMI Government and the monthly funds transfer confirmations, OPA found the listing of all claims:

- did not have any identifiers that reference the monthly funds transfer confirmations for reconciliation purposes;

- did not have any identifiers that reference the 15% access cost fee automatically withdrawn each month; and

- had multiple erroneous transactions that were identified by Vendor 9 and were automatically offset in the next month without concurrence from MRSO and/or DOF.

“Through OPA’s analysis and interviews conducted, OPA noted that Vendor 9 automatically withdraws payments from the revolving account without invoices being reconciled or approved by MRSO to ensure accuracy and validity. Documents reviewed by OPA indicated erroneous transactions that were corrected and addressed in the subsequent month by Vendor 9 without concurrence from MRSO and/or DOF. The lack of internal controls to maintain, review, and reconcile payments timely to identify these erroneous transactions puts the CNMI Government at risk for potential fraud, waste, and abuse. In addition, the lack of reconciliation puts MRSO at risk of not properly recording potential outstanding balances for other MRSO vendors.”

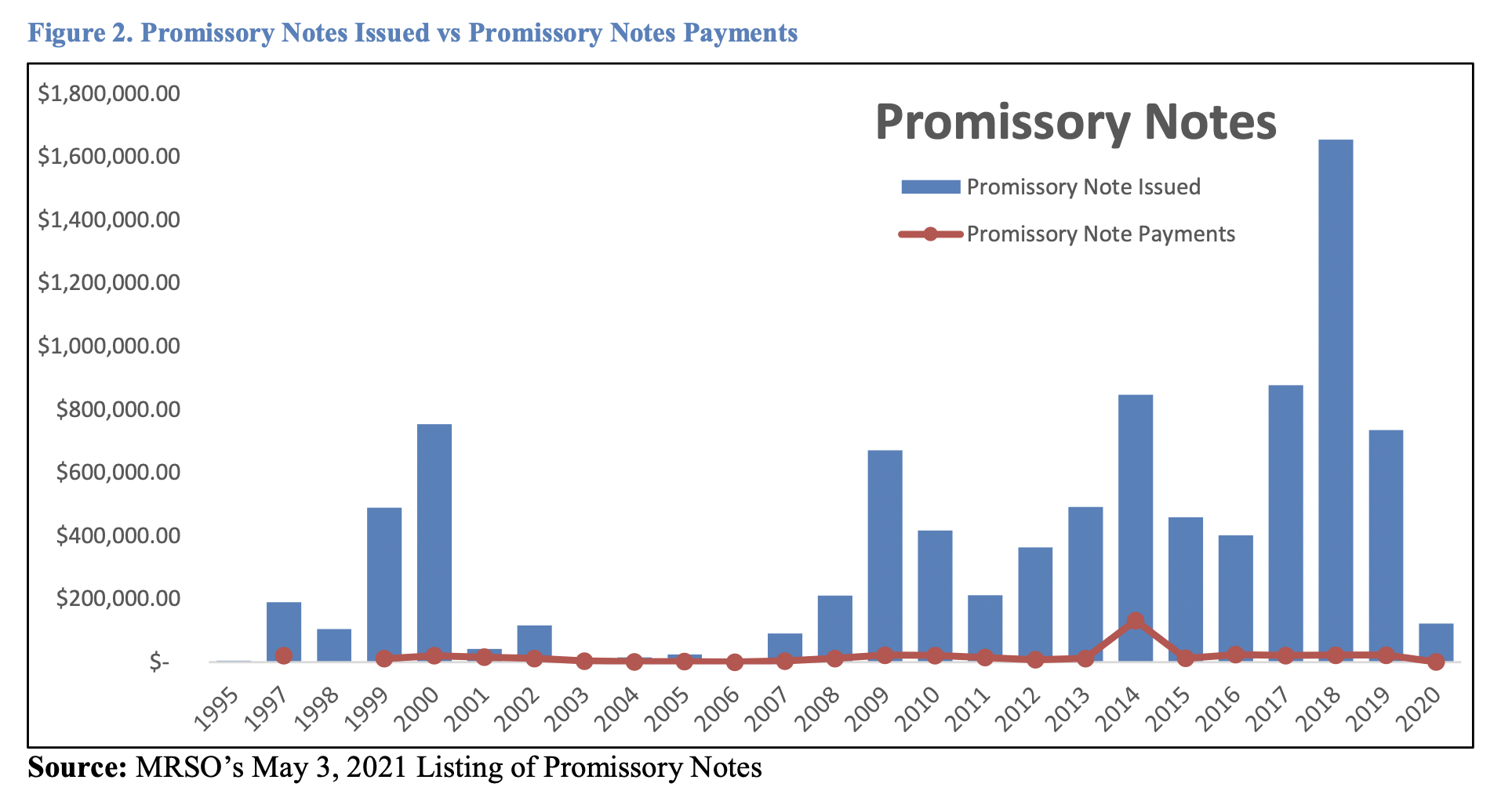

Torres issued $1.6 million in illegal promissory notes during election year

While the MRSO was under his direct supervision, the audit states Gov. Ralph Torres’s office issued $12 million in illegal promissory notes, $11 million of which remains uncollected and likely uncollectible.

“Based on the listing provided, about 630 promissory notes amounting to an estimated $12 million were executed,” the audit states. “However, about 270 promissory notes reflect partial or full payments equating to an estimated total of $420,000. The remaining estimated $11 million is outstanding as of May 3, 2021.”

OPA provided a chart of the promissory notes, which began in 1997. The majority of the notes were issued, when Mr. Torres assumed office in 2015, spiking at $1.6 million in issuances the year of his election in his own right in 2018.

Travel expenses unjustified

“MRSO’s internal policy and 3 CMC § 2199 states specific health conditions that an approved medical referral patient must meet in order to be entitled to a family or friend escort at the government’s expense.

“As previously discussed, 119 samples were referred to locations outside the CNMI with either a medical escort, family or friend escort, or both. Of the 119 samples, 38 samples did not have the referring physician’s justification requesting that a family or friend escort be provided. Of the remaining 81 samples where the referring physician’s justification was provided, OPA could not determine whether the physician’s justification(s) comply with MRSO’s internal policy or 3 CMC § 2199.”

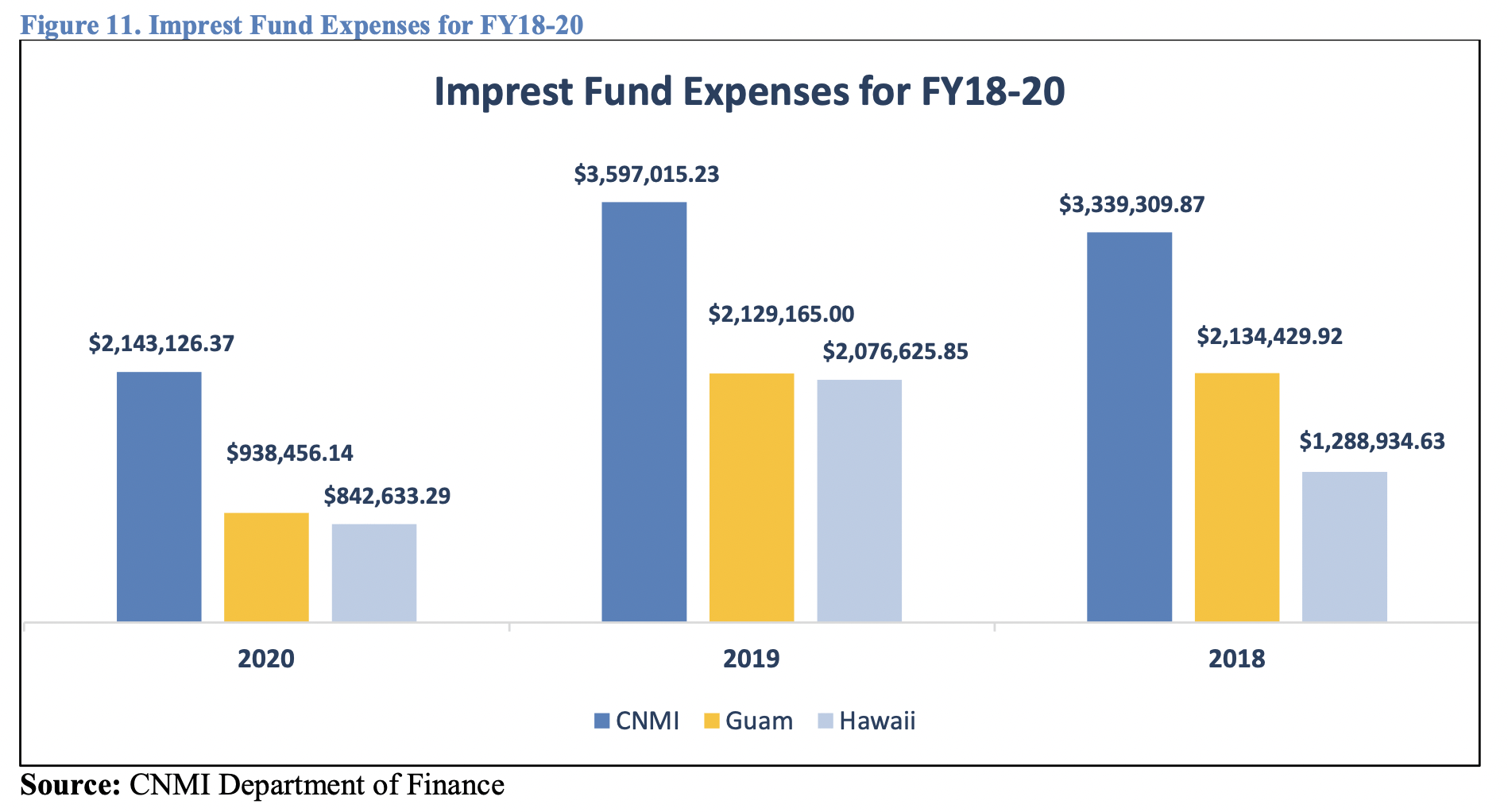

Bulk of overspending was for unjustified petty cash

According to the audit, the majority of the MRSO’s overspending in Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019 occurred because the Saipan, Guam, and Hawaii MRSO offices drew down millions in petty cash through a so-called ‘imprest fund.’

This imprest fund allowed each of the three offices to draw down $50,000 at a time for expenses such as airline tickets, subsistence allowances, operations of the office, and car leases and fuel. It acts like a petty fund. There’s a significant gap in internal control on this $50,000 fund, though: it can and was replenished without limit. According to the audit, the Saipan office drew down $3.6 million and $3.3 million in petty cash in Fiscal Years 2019 and 2018, respectively. The Guam office drew down $2.1 million in FY 2018 and again in FY 2019. The Hawaii office drew down $1.3 million in FY 2018, then shot up its draw down to $2 million in FY 2019.

Though the audited financials for FY 2020 were not available at the time of the audit, documents show the Saipan office drew down $2.1 million in petty cash that year – the full amount of the MRSO’s budget for FY 2020. The Guam office drew down close to $1 million, and the Hawaii office drew down $842,633.

“Based on interviews conducted, OPA learned that the replenishment of the $50,000 imprest fund account for each of the offices may occur more than once a week and is never denied,” the audit states. “Furthermore, a review of the data provided by DOF reflects a significant amount of expense made using the imprest fund accounts. The lack of standard operating procedures for the usage and replenishment of the imprest fund accounts poses a risk of improper use of the imprest funds.”

The Guam office, which has been headed by one of Gov. Torres’s most vociferous political supporters, was accused in the audit of operating at a risk for misuse and abuse of public funds, fraud, and waste.

“[T]he Guam satellite office does not have a universal inventory log. Based on the interview and further review of the documents provided, OPA notes that these listings are not in sequential order,” the audit states. “The lack of one universal inventory log puts the Guam satellite office at risk for misuse and inhibits timeliness of reconciliation. In addition, the lack of internal controls to monitor and document used, voided, stale, or unused checks leaves the office at a risk for fraud, waste, and abuse of government funding.”

MRSO relocated since audit

The MRSO was relocated from the governor’s office back to the CHCC in the wake of the audit.