Is Guam ready to end the state of public health emergency, and all that entails? What should senators consider, as they accept public input tonight on a resolution to end the emergency?

According to the governor’s office, more than 95 percent of the eligible population is vaccinated, and the Omicron surge is behind us. Testing and mass vaccination clinics have winded down; but the logistics of these monumental undertakings remain on standby, just in case. Perhaps, from a public health standpoint, the emergency is over. But the public’s health isn’t all that’s been affected by this pandemic. Consequences spill considerably into the realm of family finances, when you consider premium pay for workers, supplemental food stamps, and direct aid to those most in need.

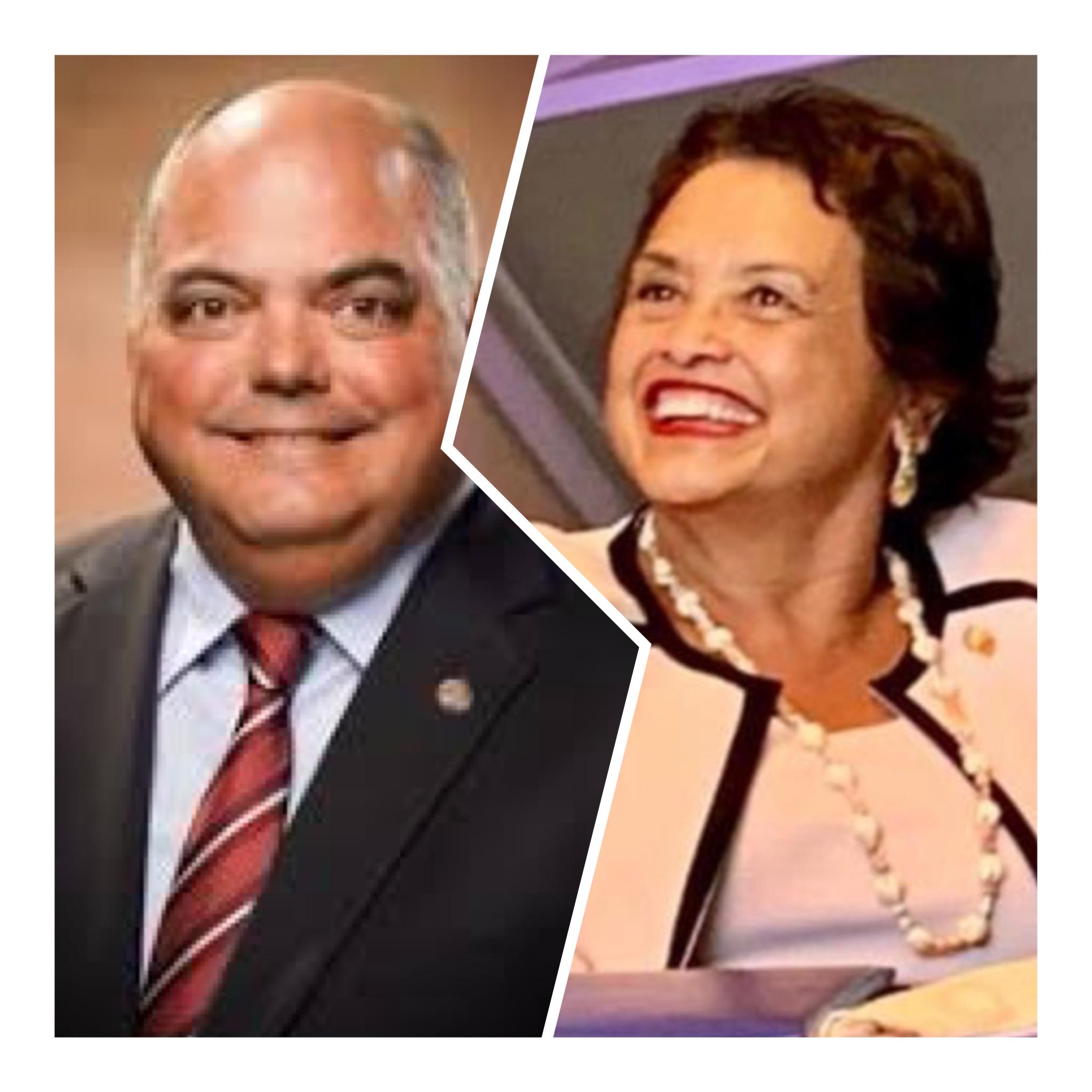

Speaker Therese Terlaje, who currently is acting lieutenant governor while Josh Tenorio is off island, publicly issued a letter to Gov. Lou Leon Guerrero last night. Referring to her executive order establishing end protocols for the two-year-old mask wear mandate, the speaker rebuked a section of the order’s non-binding findings that criticized the legislative resolution.

“E.O. 2022-09’s criticisms of a pending Resolution and the Legislature in general are potentially distracting to the public and detract from your rationale for lifting of restrictions and the extension of the public health emergency,” Ms. Terlaje wrote Ms. Leon Guerrero.

In several paragraphs, the governor lambasted senators for not understanding the consequences of their proposal to end the public health emergency (a resolution sponsored by all but one republican senator, and authored by Sen. Chris Duenas).

She listed these consequences, and some are cause for further thought.

But why did the governor wait until the eve of this resolution’s public hearing to inform the public what is at stake here? And is the speaker right? Is the governor setting an end protocol for her mask wear mandate as a political response to the Duenas resolution that will revoke her powers?

The Emergency Health Powers Act, enacted two decades ago by the Guam Legislature, gives the governor of Guam broad and sweeping powers to prevent, detect, manage, and contain public health threats. She can consolidate government resources together with private property she has the authority to seize during such a state of public health emergency. She can mobilize clinics, restrict movement, suspend statutes that get in the way of efficient response, skip over tedious procurement regulations in the attainment and appropriation of resources, institute curfews, isolate the sick, quarantine sectors, freeze prices, and provide all types of aid without the burden of a normal government bureaucracy or respect for due process at play.

And she has done all these things – used all these tools at her disposal – in one form or fashion and for varying periods of time since she declared a state of public health emergency on March 14, 2020. That was more than two years ago. And aside from the mobilization of resources, the use of abbreviated procurement authority, and the mask wear mandate, the governor has relinquished these tools.

“Executive Orders during emergencies are critical tools for rapid emergency response and critical public education,” Ms. Terlaje stated in her letter. “They should not be used as political tools.”

“I am aware of recent efforts in the Legislature to pass a resolution to end the public health emergency pursuant to the Emergency Health Powers Act,” the governor stated in her executive order on the mask wear mandate. [T]he legislative resolution is short-sighted and demonstrates a lack of understanding of, and appreciation for, the monumental multi-agency effort involved in activating, coordinating, and operationalizing a dynamic pandemic response. [U]nder the EHPA, the Governor’s declaration of an emergency activates a comprehensive government response for the prevention, detection, management, and containment of public health threats in ensuring an effective and timely response to a public health emergency.”

The speaker was unimpressed by the rhetoric.

“I do not believe the references made to a Legislative Resolution which is still pending public input via a hearing are relevant or necessary to the purpose and goals of the Executive Order,” Ms. Terlaje stated in her letter.

“[T]he drafters of the legislative resolution have not considered the broader implications associated with ending the public health emergency,” the governor said. At a snap news conference the governor hosted today (Wednesday), she went even further:

“It seems like Sen. Chris Duenas woke up one day and said, ‘Oh, I think it’s time to end it.’ On what information? On what conditions? On what science? Because the lives of people are at stake. No joke.”

Asked why her administration waited so long to provide information to the public about the consequences of ending the state of public health emergency, the governor explained frankly, “We were just so busy … I suppose, it just wasn’t something that came to mind, nothing that triggered it.”

And though her motives would be less questionable had she released this information before last night (Kandit asked the governor’s office more than two weeks ago what would be affected aside from resource mobilization if the public health emergency were to end abruptly), the contents of the governor’s executive order might beg reasonable people to give pause and proper thought to the legislative resolution.

At the very least, the governor raises a relevant point that senators over the past two years have had every opportunity to enact statutes to guide Guamanians gradually out of a state of public health emergency, but did not.

Here are the points from the governor’s order, verbatim:

WHEREAS, the EHPA, like the Model Act before it, is designed to facilitate a rapid and flexible response in light of the community’s needs during a public health emergency. The EHPA has enabled us to coordinate critical services during this emergency, including mass testing clinics, mass vaccination clinics, and ultimately treatment clinics. It has empowered us to identify issues affecting more vulnerable populations within our community and direct resources to address them. It has enabled us to fill shortfalls in personnel by pooling health care providers from other agencies to assist in our response efforts; and

WHEREAS, under the EHPA, I have issued numerous executive orders to address diverse issues relating to the pandemic that fell outside the scope of direct medical response, including the prohibition on price gouging, the authorization for overtime to our overextended government frontliners, and the waiver of licensing and permitting requirements for additional health care personnel assisting in the performance of vaccinations, treatment, examination, or testing. I have ordered that government agencies, including the Legislature, may hold public meetings via teleconferencing. I established and ultimately suspended a moratorium on foreclosures and evictions, implemented differential pay processes for essential employees in close proximity to infected populations, enabled DPHSS to establish temporary guidance allowing for importation and distribution of COVID-19 commodities, and temporarily suspended examination requirements for our teachers; and

WHEREAS, 10 GCA § 63500 states in relevant part that, as Commander-in-Chief of the Guam National Guard, I may order the Guam National Guard into active military service during a state emergency. In the absence of a state emergency, my ability to activate the Guam National Guard is constrained to affairs of the state, state ceremonies, or other territorial activities or duties. The Guam National Guard, which I activated pursuant to the EHPA, has proven to be an incredible resource during the pandemic, helping further focus our efforts efficiently and quickly, organizing and executing critical missions to ensure the success of our pandemic response. They are funded federally until July 2022, but are not otherwise activated for state duty outside of the public health emergency that the sponsors of the legislative resolution seek to end. The majority of our guardsmen serve other duties when not on active guard duty, and mobilizing and demobilizing these forces requires time that we simply do not have during a pandemic. The legislative resolution does not adequately account for the impact that deactivating and reactivating would have on the lives of our guardsmen; and

WHEREAS, most of the measures identified above could have been implemented by legislation but were not. While it is true that, unlike the Executive branch, the Legislature does not have the operational capacity to effectuate a rapid response to emergency needs as they develop, the Legislature is empowered to pass bills to perfect the transition of these measures to a non-emergency state; and

WHEREAS, while other U.S. jurisdictions have ended their COVID-19 public health emergencies, their legislatures—recognizing that such an action carries consequences for the numerous initiatives and programs established from the declaration of an emergency— passed prior legislation to ensure the continuity of such services and programs, or implemented sunset provisions to allow the agencies responsible for implementing response measures with an opportunity to transition their initiatives to regular operations; and

WHEREAS, the sponsors of this legislative resolution have failed to transition emergency measures to permanent agency operations; and

WHEREAS, to be clear, ending the public health emergency would also not give the Legislature power over grant monies received pursuant to the American Rescue Plan Act (“ARPA”). However, the Executive branch’s use of these funds is still subject to Federal oversight; and

WHEREAS, federal rules limit the use of ARPA funds to categories of spending that specifically address the COVID-19 pandemic, such as replacing lost public sector revenue, responding to the negative economic impacts of the pandemic by supporting individuals and households, businesses, and industries, and providing premium pay for essential workers; and

WHEREAS, it is for this reason that I have, time and again, rejected language in proposed legislation that purports to direct the spending of ARPA funds, especially for items that, on their face, are not related to the public health emergency. It is for this reason that I have declined to implement broader categories of direct aid that cannot be legitimately traced to individuals and households that were presumed to be negatively impacted by the pandemic; and

WHEREAS, ending the public health emergency would have a significant impact on another type of federal aid our island currently receives — Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (“SNAP”) supplemental emergency allotments; and

WHEREAS, in March 2020, Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (“FFCRA”), allowing the U.S. Department of Agriculture to issue emergency allotments to SNAP recipients during the COVID-l9 pandemic; and

WHEREAS, the FFCRA provides that such aid is available based on a public health emergency declaration by the Secretary of Health and Human Services under Section 319 of the Public Health Service Act related to an outbreak of COVID-19 and, critically, “the issuance of an emergency or disaster declaration by a State based on an outbreak of and Guam is approved to receive on average $2.3M in monthly emergency allotments under SNAP. which affects over 15,000 households in Guam. It is true that states such as Florida, Idaho, Arkansas and Montana have stopped issuing these emergency allotments, but it cannot be overstated how critical these funds are to our indigent population. This aid is important to recipient families, and it is important to me. If the sponsors of this resolution intend to proceed without resolving the SNAP emergency allotments, they should be held to account for their decision to cut off this aid to thousands of our most vulnerable families during a global pandemic.