Read this week’s issue of Spotlight by clicking here.

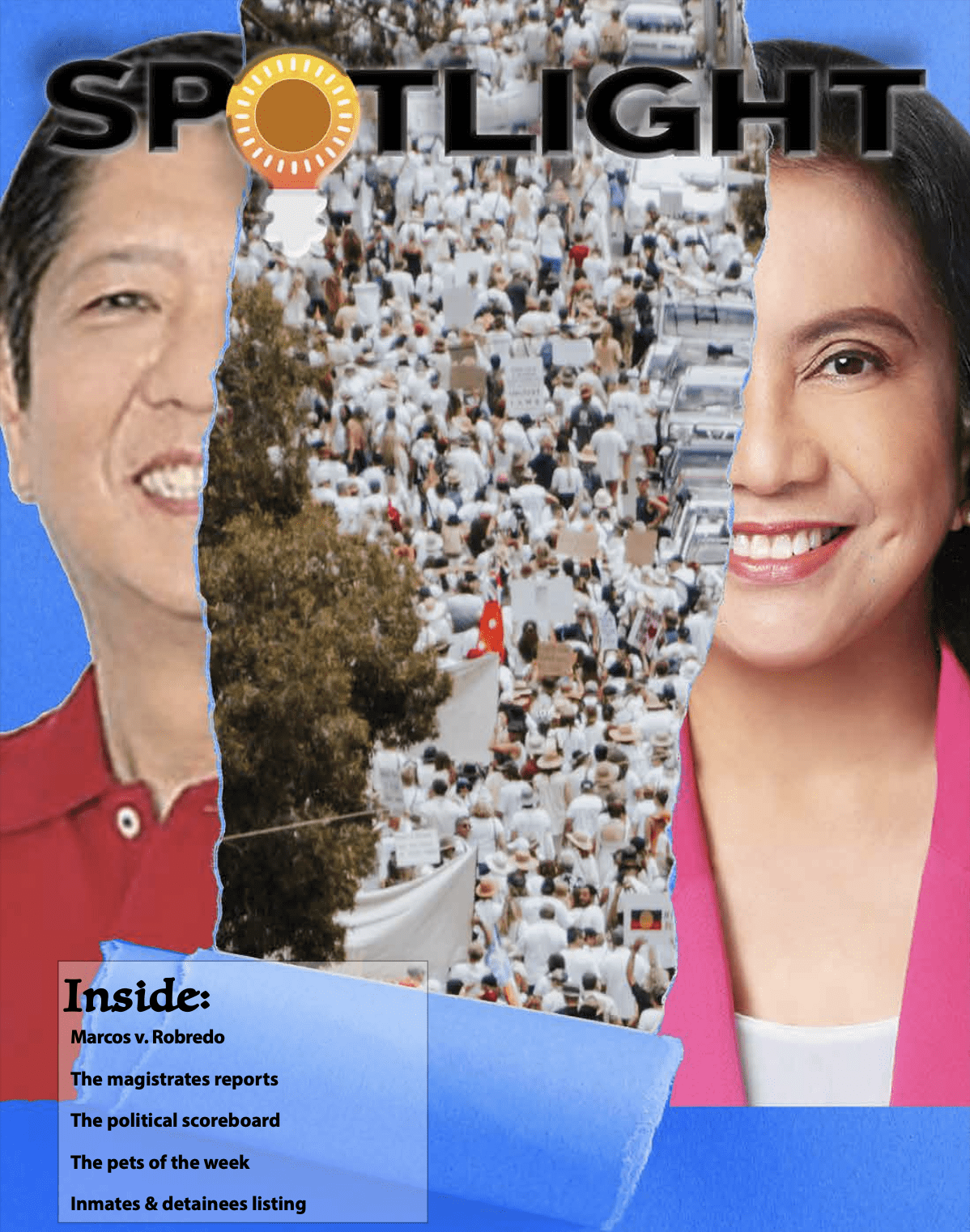

Marcos v. Robredo

The race for president of the Republic of the Philippines is tightening as Filipinos prepare to vote Monday. The election is a rematch of sorts from 2016, when then-Congresswoman Leni Robredo inched out a victory over then-Sen. Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. to become vice president. It was a come-from-behind victory, with national polling for months prior to the election showing Marcos would win the vice presidency by a landslide.

At the time, Ms. Robredo’s victory was a sigh of relief for Filipinos afraid of the return of the Marcoses to national executive power. HIs father, Ferdinand Marcos, was overthrown by a People Power Revolution in 1986 following a 21-year presidency and 14-year iron grip rule on the country. In 2016, however, Mr. Marcos’s campaign was nearly effective in reversing the contempt most voters held against his father 30 years after the revolution.

After 30 years, many Filipinos had grown increasingly contemptuous against the corrupt oligarchs whom democratically-elected presidents did close to nothing to rein in. In fact, at least two of them – Joseph Estrada and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo – faced charges of corruption for their role in advancing the corrupt agendas of the elite in Manila. On a side note of irony, those same former presidents have aligned themselves with Marcos.

For many Filipinos, as time grew between the Marcos regime and democratically-elected government, so too did their wonder whether life was better under the dictator.

“It’s been a long time, so people forget what happened,” Reynard Arcillo, 57, said. “So many people disappeared. So many of my countrymen were murdered in that regime. But Filipinos are very forgiving, some will say. I just believe too many are willing to forget how bad it was.”

By 2016, the memory of the Marcos years appeared to fade with a narrative deployed by a nearly-effective social media strategy that tapped into a fundamental question for Filipinos: Are you better off today than you were 30 years ago?

In the end, that narrative did not prevail toward an election victory for Bongbong Marcos, and Ms. Robredo was elected instead.

But, after six years, that narrative has grown.

“There’s more corruption now,” Cecilia Marquez, 44, said. “Maybe there’s corruption in Marcos’s time. It was the wife. It was Imelda. But now it’s everywhere, and Filipinos are still living in poverty!”

A mantra has become commonplace in debates Marcos supporters have with supporters of his opponents: The sins of the father should not be assigned to the son. Mr. Marcos himself has not placed himself in a position to be challenged about this message; he has refused to debate Ms. Robredo or any of the other eight contenders for the presidency.

So, what would have been a national discussion among candidates has instead become a war of information and disinformation among Filipinos on social media.

The Troll Farms

In 2016, the American people encountered their first widespread assault on free and fair elections. Sprawled throughout the United States on computer screens and mobile phones was foreign interference in the American campaign season that ultimately led to the election of Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton. Unbeknownst to the voting public was the fact that Russian and Chinese operatives intent on ruining American democracy had systemized and mechanized disinformation directly into the homes and offices of voters with Facebook accounts.

Highly-trained data miners teamed with message strategists disguised themselves online as Americans, created pages, cultivated followers with innocuous postings that progressively became political, then created and steered narratives. The phenomenon caught both Facebook and the FBI by surprise.

We also know these same activities were happening within the Philippines using Philippine-based troll farms. And as the years have gone by, that activity has increased. It is now at a crescendo in this final week of the election.

The Rewriting of Philippine History

The first part of the troll farm campaign was simple, but had global and lasting effect. It was a rewrite of Philippine history under martial law. It began with a softening of the freedoms denied Filipinos in those years. Then a rationalization for the deaths and disappearances of political dissidents. Then a romanticization of a better life that came at the expense of the late dictator’s arch-nemeses, the Aquinos.

Every story of heroism needs a villain. In the turning of Marcos into a legend, whose memory was wronged by an elite establishment intent on overthrowing him for their own political and financial gain, the villain became two dead presidents, whose presidencies spanned the gap between EDSA I and the pre-Duterte period.

It did not take much for troll farms to reset the online conversation about the Marcos years versus the post-Marcos years by simply marking the rise of corruption, poverty, and crime from the presidency of Corazon Aquino to that of her son, Benigno Aquino. It was a clean, linear argument.

And once the current Vice President, Leni Robredo, began to pose a threat to Bongbong Marcos’s bid this year, the troll farms went for the next plot in the political equation: that Robredo simply is a representation of all things Aquino, elite, and establishment.

Not everyone is buying it, though.

“What sensible and logical individuals find hard to respect are opinions based on falsehoods and fabrications because, let’s face it, those are simply lies passed on as abstract ideologies to those who would fall for it,” Eduardo “Doods” Tuason quoted Matt Lester Matel on a Facebook post regarding the elections today. “It is our duty as responsible citizens to correct them.”

Robredo’s momentum in these final weeks is showing evidence that Philippine voters are defying the Neo-Marcos narrative. For her supporters, she is not a continuation of anything.

“She’s a game changer,” Dr. Cyd Coloma said in a debate Kandit hosted among supporters of the two presidential frontrunners in our studios. What she meant was that Robredo would be a new kind of president; one not beholden to the establishment, and who did not come from the elite ruling class.

But what of the notion that corruption, poverty, and crime have increased dramatically since EDSA I? The claim seems undeniable.

A New Society

The 1973 patriotic hymn, Bagong Lipunan (written by Marcos), has made a comeback among Filipino voters harkening to a promise the Marcoses literally brought cross-country in the 1970s through this song. If martial law was the stick, then his so-called democratic revolution was the carrot.

The late dictator promised to build a New Society that would remove the oligarchs, who had grown in wealth and power to suffocate Filipinos. Economic freedom is what he would give to his countrymen by ridding the nation of its most powerful and influential families.

“Manila was owned by 12 families, including the Catholic Church, and he wanted to change that,” a personal friend of the Marcos family stated on condition of anonymity. “Marcos used poetry a lot, and in many ways it did give hope to people.”

That hope is what Bongbong Marcos is trying to instill with his promise of a New Society under his presidency. And why not, his supporters ask. Why should Filipinos not enjoy the promise of a president who would regulate the elite and the powerful, concentrate power in his hands, and redistribute wealth to create a strong middle class?

The irony is, Ms. Robredo’s entire platform makes this promise with one glaring subtraction in the equation: she does not want to concentrate power in her presidency. Instead, she counters with transparency as a cornerstone of her governing pivot.

Can the Philippine presidency achieve economic health for the masses and a reduction of crime and poverty without the executive power wielded under martial law? It seems that for half the country, voters have lost patience with the democratic model that has existed since Cory Aquino. And for the other half, there is the belief that the Republic of the Philippines has not yet benefitted from the presidency of a game changing woman in pink.

Which side will prevail? We’ll likely know Tuesday morning.