Click here to read Issue 14 of Spotlight

I’ve been involved in every Guam gubernatorial campaign since 2002; lost twice. The first was in the primary election of 2002 under the Tony Unpingco-Eddie Calvo ticket. I was then recruited into the Felix Camacho-Kaleo Moylan campaign; and we won the general election.

The second was in the primary election of 2018 through the Dennis Rodriguez-David Cruz, Jr. campaign.

Every one of those elections from 2002-2018 had varying degrees of negative campaigning. And I don’t mean the contrasts in records, or the criticisms of platforms one candidate has against the other. I’m talking about the lies, innuendo, and skeleton-throwing tantrums of campaign surrogates (they’re called ‘trolls’ nowadays since the movement of the campaign battlefield to email, then to Facebook) against the opposing candidates. They involve themselves in what is aptly called as ‘black operations,’ known affectionately by the operatives as ‘black ops.’ The operatives’s battlefields are media best suited at the time to delivering the laser-focused messages through which they hope to command a narrative. Sometimes it works, many times it appears to work with unintended consequences and backlash at just the right time, and most of the time it fails.

In 2002 and 2006, the battlefield was waged on talk radio, direct mailers, and on the windshield’s of people’s cars. Those general elections saw the matchup between Felix Camacho and Robert Underwood twice. Both times, Camacho’s foes attacked his wife and his daughter in a black campaign to smear his credibility, character, and integrity. Both times, Underwood’s enemies used talk radio, direct mailers, leaflets on windshields, and even a primetime commercial to use sentences from his doctoral dissertation to paint him as a racist against Filipinos.

Obviously, voters weren’t very keen on the personal attacks against Mr. Camacho’s family. As for the race card, that worked very well. Underwood lost handily in every northern village, especially Dededo, and in Agat; areas populated heavily with Filipino voters.

The campaign landscape shifted in 2010; email was all the craze. The dynamics were different as well. The incumbent lieutenant governor, Michael Cruz, was campaigning against Sen. Eddie Calvo to win the republican primary and challenge former Gov. Carl Gutierrez. Shortly before the primary, an email went viral. The email made sinister allegations against Cruz and his running mate, Sen. Jim Espaldon, regarding a sexually-transmitted disease and drug use. Naturally, the Calvo campaign denied any knowledge of the attack and instead blamed the Gutierrez campaign for conspiring to split the republicans knowing Cruz was the weaker of the candidates. The theory, according to the Calvo campaign, was triangular black ops.

Sometimes – and this is particularly true when one party has a contested primary, and the other party only has one candidate running unopposed for the nomination – the unopposed campaign’s surrogates will launch an attack against the weaker of the other party’s candidates during the primary. It is disguised to look like the stronger candidate’s surrogates made the attack. It’s brilliant, really, if you don’t get caught. You manage to cause further discord between the opposing party’s challengers. All you have to do after the primary is embrace the loser, and it becomes that much easier to win the general election.

In 2014 and for the first time in gubernatorial campaign history on Guam neither party had more than one candidate for governor. It was Eddie Calvo versus Carl Gutierrez, and it was one of the cleanest campaigns we’ve ever seen. Sure, there was mud, but compared to the campaign to come, the two governors’s fight in 2014 was angelic.

In 2018 everyone lost their minds. Four gubernatorial tickets competed for the democratic nomination: Rodriguez-Cruz, Frank Aguon-Alicia Limtiaco, Carl Gutierrez-Fred Bordallo, and Lou Leon Guerrero-Joshua Tenorio. The winner of that campaign would go on to challenge the lone republican contender: Ray Tenorio-Tony Ada. There was an active attempt to keep Rodriguez from running by siphoning any known person on his short list for lieutenant governor. The popular senator secured the commitment of a University of Guam executive as his running mate. Word of the union went around political circles, and she was targeted. Within days, she had pulled out, leaving Rodriguez in limbo. Then, when he chose Colonel David Cruz, Jr., another attempt was made to disqualify the decorated military man.

The usual suspects of black operations targeted Joshua Tenorio for being a gay man. That went nowhere. Other surrogates went after Aguon and his family, swirling innuendo about his marriage and children.

And then there was the federal investigation into the Aguon campaign’s use of troll farms from the Philippines to proliferate what’s come to be called as ‘fake news’ via Facebook. It almost worked. Not only did Aguon nearly win the primary election, but he also forced a runoff election after the general when he wagered a near-effective write in campaign.

The amount of dirt thrown from the primary to the runoff would have scared Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. The 2018 election was the dirtiest one had been in a long time.

Believe me, when I tell you this 2022 campaign already is the dirtiest. Funny thing is, it seems the dirt that’s being thrown isn’t making much of a difference. It may even be backfiring.

This is the first gubernatorial election in 20 years that I’m not part of. But, if I were (and I’ve been on the winning side more often than not), I’d hand out some free advice: concentrate on your candidate’s strengths, anticipate the criticisms of weaknesses, and shore up those challenges.

Hell, here’s some consulting, free of charge, to each campaign:

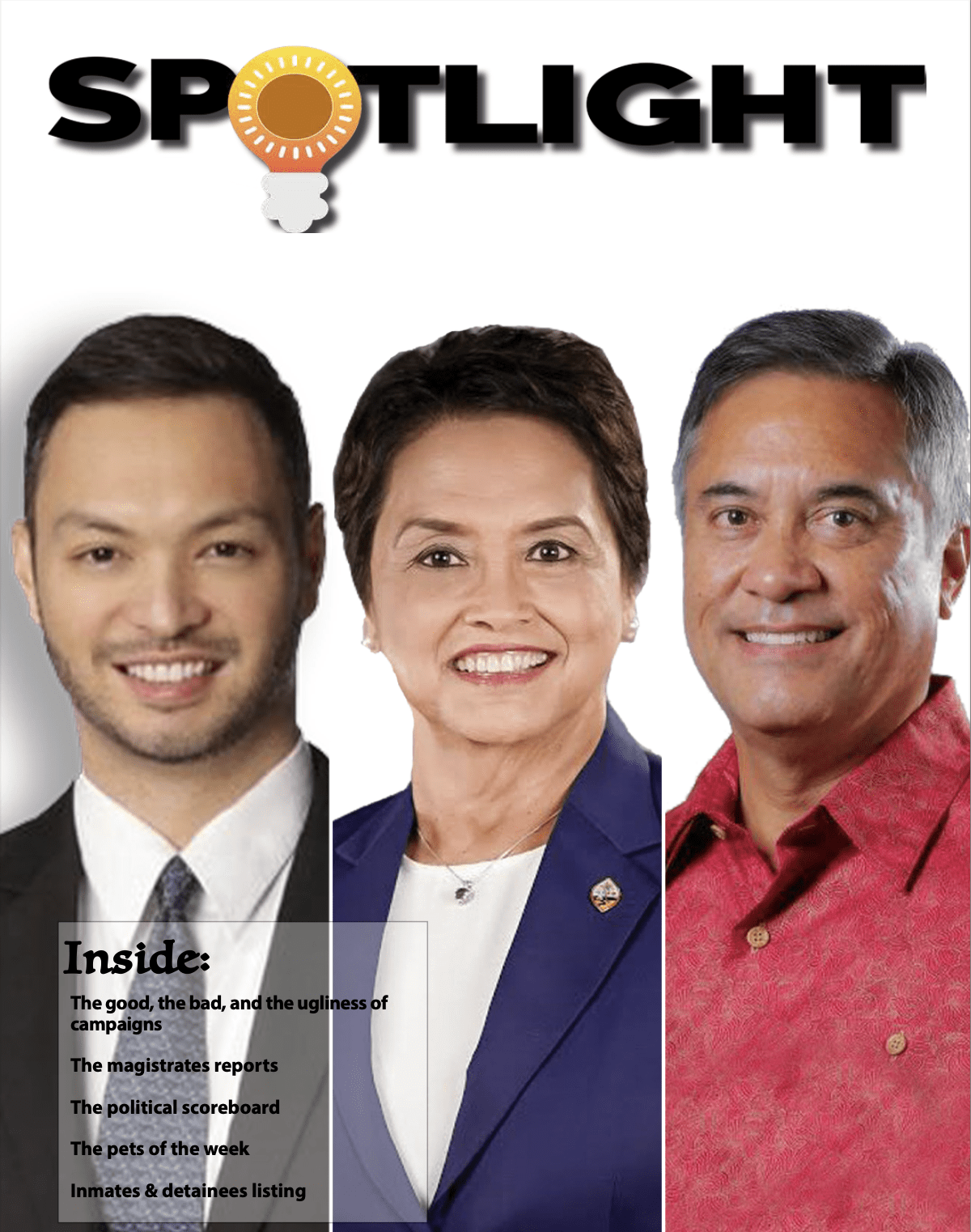

Lou Leon Guerrero’s leadership in crisis

Gov. Lou Leon Guerrero, a nurse by trade, should be played up as the leader we needed at just the right time. Pandemics are centennial events. No one saw coronavirus coming our way in 2018; it never even came up as a possible issue on the campaign trail. But, when it happened, the governor acted and arguably made decisive moves.

Her campaign should praise the effort to contain the spread of the disease, then to inoculate the population just as the Delta variant was making its way around the world, essentially avoiding additional deaths.

Ms. Leon Guerrero’s leadership in crisis is the sale she can make to the Guamanian voting public. Marry that with strong imagery of a maternal, caring, and compassionate person, and her campaign has half of what it needs to win.

The governor can also claim a level of fiscal prowess. Prior to the pandemic, her administration managed to reduce the government of Guam’s nearly-$90 million deficit, which likely improved GovGuam’s ability to pay its vendors timely and ensure payroll during the low collection months.

The governor also has another strength: Josh Tenorio. While she has been managing the coronavirus era, Mr. Tenorio has busied himself with social services issues ranging from the growing homelessness problem to the drug epidemic. These are campaign gems, to be sure.

Overcoming weaknesses

The challenge the Leon Guerrero campaign faces is the answer to the question, ‘what’s next?’ You see, this has been a protracted ‘crisis,’ and for many, there hasn’t been a crisis in quite a while. Voters will inevitably want to know whether she can lead beyond this so-called crisis. Sure, she was the leader we needed at just the right time; but that time is over, critics could effectively argue.

Her strength doubles as her weakness for 2022: she oversaw the response to a pandemic, but because it consumed three out of her four years as governor, it’s largely all she did. Meanwhile, the cost of living and the battered economy need a different type of leadership, one that is visionary, unchartered, and motivated.

Guamanians face joblessness, incomes inadequate to afford housing, utilities, car payments, and food, and age-old problems that are quickly making a comeback to the top-folds of the newspapers: crime, education woes, and even the dilapidating conditions of the fragile health system.

The governor can quickly point to programs her administration has started to help families to cope with these extraordinary burdens. The campaign can even point to the quicker pace of tax refunds. There’s one glaring problem they will face, when they point to these: one of her opponents is the chief reason she has the money to fund these programs and those tax refund payments, and he advocated for those uses before even she did.

We don’t even have to wait and see for this perforated strategy to play out. The governor’s ironic use of federal funds to create and play the ‘Thank you for the Prugramman Salappe’ commercials littering the airways already has been met with Congressman Michael San Nicolas’s ‘Thank you for the federal funds’ spots.

And then there’s the unanswered questions about the use of federal funds, and how many of the governor’s supporters ended up getting lucrative contracts paid with federal funds. Sooner or later, her opponents are going to make corruption a campaign issue, and she best be prepared to answer the questions that will come; including those an audit raised about her son in law.

Felix Camacho’s leadership beyond crisis

If you want tested leadership that has overcome crisis and taken Guam beyond one, then Felix Camacho is your man. That’s how I’d strategize his message if I were on his campaign.

Former Gov. Felix Camacho also entered office needing to cure a crisis that never was an issue on the campaign trail. One month after his election in November 2002, and one month before his inauguration in January 2003, Guam was nearly destroyed by Supertyphoon Pongsona. The man literally took office by candlelight, as more than 95 percent of the island was without electricity, running water, and fuel. Thousands of people were displaced by the storm.

Even before Pongsona, GovGuam and Guam society were on the precipice of a downward spiral. Government revenues were systemically overshadowed by growing expenditures, and a momentum toward poverty had begun to spin. All aspects of welfare – food stamps, Medicaid, and public housing – were growing along with the perverse incentives for beneficiaries to get back onto their feet. These invisible forces conspired with a government and economy on the brink of collapse following Pongsona to mount a seemingly insurmountable challenge for the newly-inaugurated governor.

But he did it. He managed to operate the government without one payless payday in that first year, when GovGuam had to force its $541 million operation into a $321 million cash reality. With the help of the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Recovery Coordination Office, infrastructure was restored within months, and the decimated tourism industry rebounded.

Federal spending also was on the rise. And thanks to Camacho’s growing relationships and networks in Washington, D.C., Guam enjoyed greater access to decision-making powers upon the announcement of the military buildup during his term.

By the middle of his first term in office, Camacho’s management of finances yielded the breathing room to embark on three ambitious and rather successful campaigns. First, he built several schools, an investment which his successors – Eddie Calvo and Lou Leon Guerrero – have not been able to match. Then, he began an affordable housing initiative, without which thousands of our people would not have been homeowners or renters at below-market cost. Finally, Mr. Camacho began an islandwide road building and pavement initiative, complete with an abandoned vehicles reduction program.

Overcoming weaknesses

Mr. Camacho’s fiscal achievements came at a price his opponents will capitalize upon. The way he balanced the government of Guam’s budget every year was simple: he didn’t pay tax refunds and the accompanying Earned Income Credit and Child Tax Credit. He also raised the business privilege tax by 50 percent in his first year in office. And GovGuam employees still remember the 32-hour workweek they sacrificed through.

If I were on the opposing team, I’d use every opportunity to remind the voting public about these shortcomings of the Camacho era. And if I were on Camacho’s team, I’d let the man talk. He has a soothing and hypnotic way with words. In 2006, he convinced government of Guam employees to rally to his side in a stunning upset against Robert Underwood by talking frankly and with this magical aura about the virtue of sacrifice. He convinced voters that the decisions he made yielded long term successes that were the result of collective sacrifice. Essentially, he turned lemons into lemonade.

Aside from that, I’d worry a bit about Camacho’s proclivity for taking trips. He was the traveling governor, so to speak, and detractors may remind the public of his use of public funds to globe trot.

As for allegations of corruption, I don’t see a stain. But, I’d be careful if I were the former governor’s campaign to be so visibly aligned with people who can be seen as wanting in on the gas pedals of power.

Michael San Nicolas’s consistent delivery of results

Congressman Michael San Nicolas will solve problems no one else has been able to manage. Without a doubt, that is what most voters believe and it is clearly what his campaign should reinforce.

Mr. San Nicolas did even what his closest supporters didn’t think was possible: get federal war claims paid, get the federal government to reimburse Guam for the Earned Income Credit, convince the Feds to include Compact of Free Association migrants in Medicaid coverage, increase Medicaid funding, and so many other legacy issues no congressman before him has been able to do in 50 years.

And he did these things while convincing members of Congress to shovel billions of dollars in coronavirus and military spending on a territory half way around the world from Washington, D.C. That coronavirus funding – and only that funding – is what kept middle-class families afloat during the pandemic. The military funding clearly is the only thing keeping the economy alive as we move away from this era.

Every program helping struggling families on Guam today is funded by the money San Nicolas secured for Guam – from the local stimulus to the gas vouchers and emergency rental assistance to child care stipends for family members who watch kids. That ‘prugramman salappe’ was ‘thanks to the federal funds.’ The quicker payment of tax refunds? His campaign should readily applaud the congressman for the additional $60 million in EITC funding that made that completely possible.

Mr. San Nicolas has been vocal about how this money should be used to bridge struggling families from the poverty of the pandemic to the return of tourism and the influx of cash from other industries that can be built. He has, several times, expressed frustration that while he was able to deliver this money to Guam, he had no control over how it was spent here… unless he were governor.

The congressman’s vocal advocacy began long before he was elected to be our delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives. As a senator, he built a reputation as a maverick, never allowing party politics or really any politics to guide his votes. He often called out corruption, even within his own party. For that, they tried to expel him. In return, voters loved him ever more.

The San Nicolas campaign should harvest the trust he’s built with voters all these years with an easy connection of dots: you can trust him to deliver on his promises.

And there are promises voters want to believe in. We want to believe a governor can bring us to the proverbial Promised Land after these long years of the pandemic. We want to believe in a plan that creates wealth for families, actually supports teaching and learning, improves access to medical care, and does something to calm down crime. If I were in the San Nicolas campaign, I’d remind people that Mike San Nicolas does what we’ve been conditioned to believe is impossible, and will do so as governor.

Overcoming weaknesses

Mr. San Nicolas faces questions of character that his opponents already are raising. The ethics complaint his former campaign manager lodged against him in the House have become fodder for a political action committee and black operations to discredit him. His former campaign manager, John Paul Manuel, accepted a cash donation in 2018 that exceeded the legal limit. Shortly after the campaign, San Nicolas decided not to bring Mr. Manuel on board his congressional office.

Months later, Mr. Manuel accused his former boss of being aware of the illegal donation. Mr. San Nicolas has denied the accusation. A preliminary report from the ethics investigator made passing mention of a second witness to the allegations, but never named the witness. The claims by Manuel have languished in Congress, allowing San Nicolas’s detractors to fan the flames against his character.

The congressman also was accused by the former Calvo administration of not disclosing a conflict of interest he had as a senator who rented Section 8 housing units. At the time of the allegations, he said he was unaware of the oversight and remedied the matter by cutting his ties with his tenants (he was a Section 8 landlord before he became a senator in 2012).

The current administration doubled down on the congressman, and in 2019 filed a civil complaint against San Nicolas and his father. Both have requested the dismissal of the complaint.

Mr. San Nicolas’s hands are seemingly tied as to his ability to address these accusations against him; both matters are pending a judicial process. The ideal situation will be for the ethics committee to adjudicate the Manuel complaint against him, and the Section 8 matter to be disposed of so that San Nicolas himself can extricate himself from what has become the latest in a long line of attacks against him.

One thing is certain: the closer Mike San Nicolas gets to Adelup, the greater and more viscous the attacks him will get.

3 Comments

Ziimmmyyy

05/14/2022 at 11:15 PM

Anyone that votes for Governor Lou again, clearly don’t know how to read. I don’t know about politics, but reading about Lou Boo in this article, made it clear I wouldn’t vote for her.

Ziimmmyyy

05/14/2022 at 11:17 PM

BOOOOO LOUU! Literally BIG BOO BOO! Biba San Nicolas and Mantanane!

Jonalyn

05/21/2022 at 4:54 PM

Biba San nicolas & Mantanane.